Researchers have established the characteristic aromas of commercial vetch – a potential protein source – for the first time.

Plant-based proteins (such as beans, peas, and lentils) have been identified as a promising solution to food security concerns – offering a sustainable alternative to traditional livestock. Due to increasingly unpredictable environmental conditions, there is rising interest in previously underutilised, more resilient plant-based protein sources, such as Vicia sativa (common vetch).

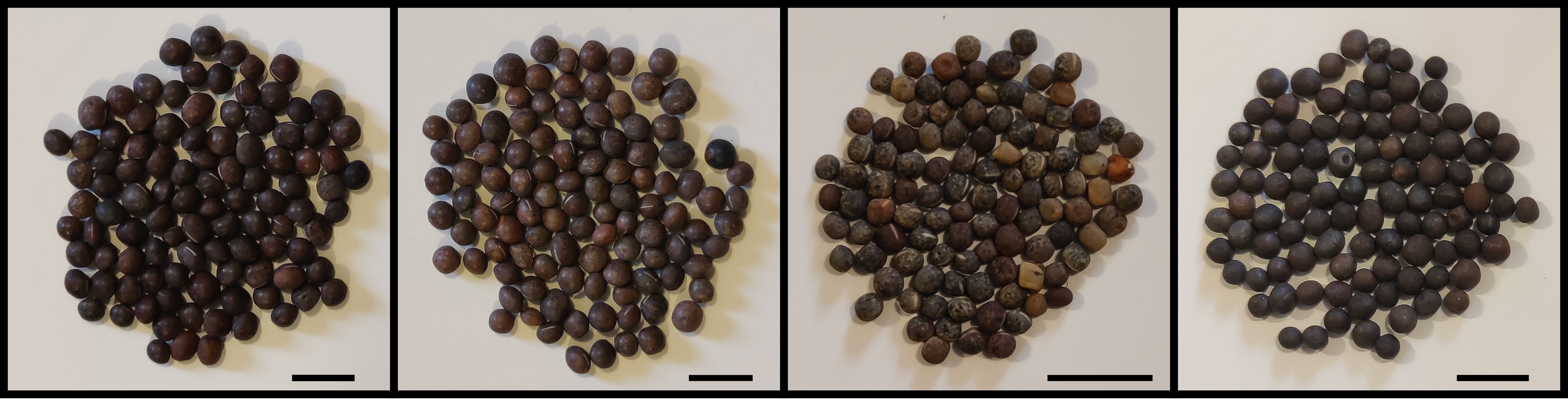

Amelia, Jose, Segetalis, Latigo

L-R: Amelia and Jose are varieties of common vetch (Vicia sativa), Segetalis is a landrace of common vetch (Vicia sativa), and Latigo is a variety of hairy vetch (Vicia villosa). When split, they all are very physiologically similar to lentils. (Image provided by Sam Riley)

“Common vetch seed is protein rich, has high amounts of essential amino acids, is a drought tolerant leguminous crop, and historically overlooked as a source of human food or animal food”, said A/Prof Iain Searle of the School of Biological Sciences, University of Adelaide. Researchers at the University of Adelaide School of Biological Sciences and University of Nottingham School of Biosciences are working to make common vetch a safe and nutritious food source – but, as Joint University of Adelaide and University of Nottingham PhD Student Sam Riley shared “it must first be deemed palatable”.

Sam is the lead author of research published in peer-reviewed journal Food Chemistry, which aimed to describe the characteristic aromas of commercial common vetch and explore the effects of processing, cooking and fermentation on flavour development. Working with researchers from the University of Adelaide and University of Nottingham, the team established the characteristic aromas of commercial vetch for the first time and provided important insights into the role of variety and preparation on flavour.

“Our research provided a robust characterisation of common vetch aroma…bringing our understanding closer to making common vetch a safe and nutritious human food source,” Sam said.

“All tested commercial varieties had little variance in volatile (chemical compounds that contribute to aroma and flavour) profiles, but wild varieties had three times higher concentrations in volatiles. The dominant compounds were found to be documented and described off flavours including pentyl furan, benzyl alcohol, benzaldehyde, 1-octen-3-ol and 1-hexanol, which are mainly associated with beany, grassy aromas. Upon processing the vetch through cooking, it was found that newly formed volatile compounds increased in overall prominence and in the case of fermentation this occurred whilst concentrations of the original off flavour 1-octen-3-ol significantly decreased, suggesting a potential improvement in palatability.”

Now coming to the end of his PhD, Sam highlighted the valuable role of the Adelaide-Nottingham joint doctoral training program in his research. “The global nature of the collaboration allowed us access to the University of Nottingham’s food hall (which is a fantastic food industry grade production facility where we fermented and processed samples) combined with the Grains for Health Joint Research Centre’s large collection of vetch varieties. The [Joint International Flavour Research Centre] also allowed us to analyse volatile profiles using SPME GCMS that would otherwise not be accessible to us.”

Other co-authors of this research are Aneesh Lale, Dr. Vy Nguyen, Hangwei Xi, Prof. Kerry Wilkinson, A/Prof. Iain R. Searle and Prof. Ian Fisk.